A child abandoned by his father becomes a petty thief by the age of 10. At 19, he is a revolutionary armed with an electric guitar positioned to take over the world. Somehow, it all went to hell.

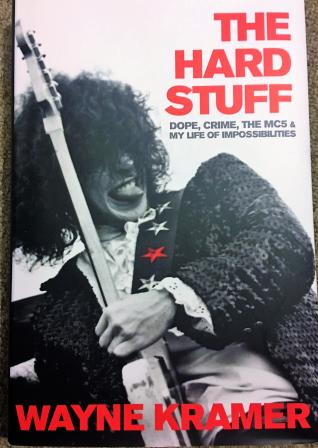

“At 25, I had flushed my fine young life right down the toilet,” reminisces Wayne Kramer in “The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, The MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities.” The book was published in August by Da Capo Press.

In the 296-page memoir, Kramer clearly points to some key markers of his existence: crucial moments during his childhood, the promise of his time with the MC5, crimes committed, prison time served and his hard-fought journey on a path riddled with temptation toward sobriety, family and the music that inspired him as a young man.

Kramer was born Wayne Stanley Kambes in Detroit in the spring of 1948, the son of a strong woman of French ancestry and a World War II marine dad whose family emigrated to America from the Greek island of Corfu. When returning home from military service, Kramer’s emotionally detached father engaged in bouts with alcoholism and eventually separated from the family, leaving the boy’s mother to work two jobs to raise her kids.

At the age of 10, he took to lifting small items from convenience stores and set about losing his virginity to his 16-year-old babysitter. It was awkward, and the guilt followed him for years. “I didn’t have sex again until I was 17,” Kramer writes. Compounding his emotional turmoil, Kramer suffered abuse through the actions of his mother’s new husband. “He was a grown man. I was a boy. The backwoods depravity was horrific.”

You could make the case what saved Kramer was his growing fascination with music – becoming entranced with the compelling twang of Duane Eddy’s electric guitar coming from the neighborhood jukebox and the jangling tones of Chuck Berry playing on the radio. “It sounded unearthly. Magical. Powerful…I wanted to play the guitar like that,” he writes.

Kramer’s 25-cent-a-week allowance was spent purchasing 45’s, and he eventually got his first guitar. At the age of 15, he met Fred Smith and the two began jamming together - “teenage boys discovering the world” – and put together a group they named the MC5. “Short for Motor City Five. We liked the name, (it) sounded like a car part.”

While his high school classmates eyed securing future employment at the local auto factory or striving for a good union job, Kramer was more interested in where the music might take him. “The guitar… both my obsession and my refuge.”

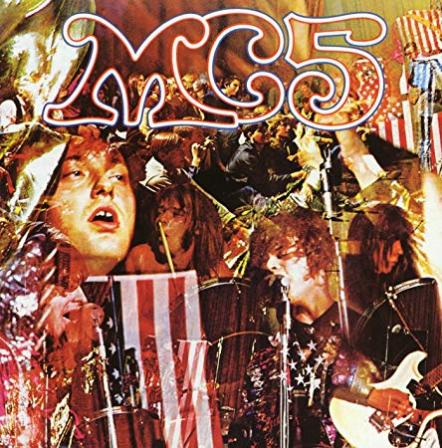

The MC5 built a following in Detroit during Kramer’s high school years, performing covers of tunes written by the Stones, the Kinks and the Who and tossing in their own feedback-laced, avant-jam textures. Through 1967 and ’68, the band lived together, played together and wrote together, building a greater regional reputation across the north Midwest. The band was also becoming more politically aggressive, railing against injustice and positioning themselves, for what they believed could be, the voice of their generation.

After catching the ear of Elektra Records Publicity Director Danny Fields and scoring an album deal, the band recorded a pair of live concerts in late 1968. After adding some sonic “embellishments” and “uncontrolled lunacy” to the previously recorded live tracks, the MC5 released their debut album “Kick Out the Jams” in early 1969.

A key moment took place when the MC5 travelled to New York City, where they were confronted after appearing at the Fillmore East by a group of political militants in the East Village taking issue with the band for not being revolutionary enough. It provided an inkling that the band’s presumed ascension to the forefront of a rock and roll led revolution was not to be.

“This was a prime example of the failure of the sixties militant mindset. They attacked their own comrades. We were on the same side, but they turned their revolutionary zeal against us,” Kramer explains. “We put our career as a band on the line for the principle of revolution as we understood it, and we didn’t end up so well. We were firebombed, harassed, beaten, arrested, jailed, and ultimately kicked out of the music business for our politics.”

Three years and two albums after their promising debut, the MC5 was no more and Kramer was left a financially broke “drug-addicted, criminal musician” who had lost his car, lost his girl and had to move back in with his mother. He fenced hot goods, sold weed and pills and burglarized homes – which got him busted, more than once. He ended up serving 2-1/2 years in a federal prison for attempting to sell cocaine to a federal agent.

“Psychologically and emotionally, being in prison changed me. I wasn’t the bright-eyed, bushy-tailed idealist anymore. Rock & roll was not going to be my solution to everything,” he says. Kramer spent the next several decades trying to put his life in order. There was a short-lived band with Johnny Thunders – during which he stumbled back into the junkie cycle – and an even briefer marriage with photographer Marcia Resnick. Kramer has little to say about his collaboration with Thunders and is silent altogether about Patti Smith, despite her being married for 15 years to his boyhood chum and bandmate Fred “Sonic” Smith, and Patti adorning her band’s “Radio Ethiopia” album with a “Free Wayne Kramer” slogan while he was incarcerated. Maybe it’s a Detroit vs. New York thing.

Kramer eventually reconnected with the father who had abandoned him as a boy and came to some hard realizations regarding the psychological scars of his childhood. “I was an angry little boy, and I grew up to be an angry young man…I had carried a myth in my head and heart throughout my entire life.” In 1995, he met journalist Margaret Saadi and eight years later, the two were married. He continued to wrestle with his demons and coped with his addictions, yearning to understand the motivations behind his more destructive actions.

The book’s opening pages cite a Nikos Kazantzakis quote describing the duty of youth as the belief of remaking a more virtuous and just world.

“Finding a way to live where drugs and alcohol are no longer necessary has allowed me to live a manageable life,” Kramer writes, searching through the existence of his own child - who is today five years old - to make the circle of his own life whole as well as to provide in his own son‘s life, the existence Kramer himself never had.

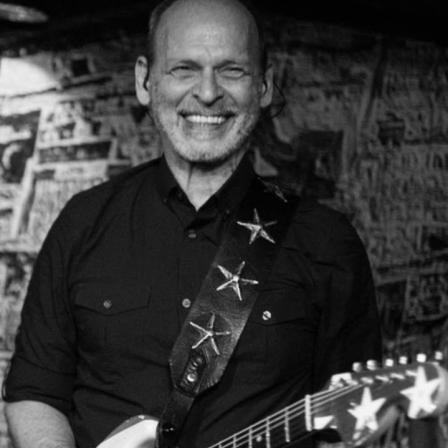

Kramer’s memoir, “The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, The MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities,” was published in August by Da Capo Press. In early September, the guitarist hit the road for a three-month tour, bringing the MC5 album “Kick Out the Jams” to the worldwide stage with a project he calls MC50.