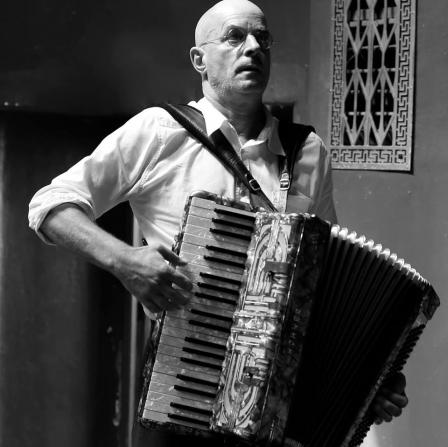

James Fearnley is the former member of The Pogues, and one of the father of celtic-punk. Now James continues his career recording the first EP of his new project “The Walker Roaders”. For the readers of Punk Globe, James Fearnley talks about the very first years of The Pogues and his music. About his upcoming TV show and the difference between projects. About his book "Here Comes Everybody: The Story of the Pogues" and about his background.

Punk Globe: In the first chapter of your book you wrote that after a few years with The Pogues and all band’s success you thought about leaving the band. Tell us about that?

James: As I say in the first chapter, the band was my livelihood, I was used to it, or inured to it maybe, and besides, I didn’t want to let Shane go, preferring to punish him for his bad behavior by dragging him around with us a few years more. I never really ever thought about leaving the band, I don’t think, until after we’d got rid of Shane in 1991 and – after Strummer was finished and gone too – we ended up, in Spider, with a singer who was even more unpredictable than Shane was. In the early days (in Chapter Twelve in the book), Jem comes to me to let me know that he wanted to leave the band. I was horrified by the thought. In answer to your other question, as to when I understood that the band had become extremely popular, I suppose I got the idea that popularity had a sort of ‘us and them’ aspect to it, when Alex Cox came to London to direct the video for ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’. He shot the band in a ‘live’ setting at, I think, the Electric Ballroom, in Camden. I remember a number of our fans coming up to us complaining about how they were being treated by Cox and the production team and the film crew, I suppose – as people who were not so important. It was an unpleasant feeling for me. We had had a solid family of supporters who seemed dedicated to us, from the days of playing at the Pindar of Wakefield, and we ended up having to basically treat them like shit by using them as ‘background’ in a video.

Punk Globe: You began your career with Shane and Shanne Bradley playing in The Nipple Erectors. What attracted you to punk music ?

James: Oh, punk music came to me, I suppose. I was more of a hippy back in the mid-to-late seventies. I had hair down to my tits until my last year at college in Ealing and then didn’t really get it cut properly until the autumn of 1977 (in order to be an extra in the miniseries ‘Holocaust’ which starred Meryl Streep and James Woods). It wasn’t long after I’d got rid of my flares that I went to the audition for the Nips. I mean, I’d loved the Jam and the Clash (not so sure about the Pistols) when they first released their records, but it was my younger brother who introduced those bands to me. Before the Nips, I played in a soul band, for a time in a ska-band and a band that I suppose you’d call ‘new wave’. I didn’t join the Nips until it was all over, really, in 1980, when the Nips were reforming, I suppose.

Punk Globe: After changing your guitar to accordion you could have save all this energy and drive the characterize punk rock. What made you to do this ?

James: I’m not sure I had all that energy anyway, to be truthful. More than anything, it was the people I found myself with – Jem and Shane to begin with, followed by Spider and Cait and finally Andrew – who were more inspiring than the music, to begin with. Not that I didn’t find the music inspiring – maybe not the music itself, but the way we played it. It was the process which I loved. We practiced hard. People have not believed me when I’ve told them that. But, apart from sudden panics about the time the pub downstairs closed, we basically locked ourselves in the back bedroom in the flat of a friend of ours, and played those songs, over and over, putting them together, with Shane, for the most part, and playing and playing. If Spider or Shane sloped off in the direction of some other activity, Jem usually chased them down during the week and corralled them back into the fold.

Punk Globe: The accordion has always been associated with traditional French music. So when you started playing, was your Irish traditions in your focus?

James: Well, French musette accordion is one of the most readily identifiable accordion sounds, which can’t help but summon up striped long-sleeved t-shirts and berets and streetside painters and strings of onions and such. But then the melodion conjure up tango and Buenos Aires bars and beef and so on, while the button-accordion conjure up metal boot-tips and decorated sombreros. The accordion’s got a lot to answer for that way, I suppose. As for my playing – I don’t know: I wanted to play as closely as I could what I heard in the music we took for our inspiration, and replicate that. Later, I concentrated on what I thought would be a good idea. I’m not a particularly adept accordion player. I don’t bother with the button side of the instrument. I’m not a solo accordionist either. It’s better to play with people. And at the beginning, it turned out we were all learning our instruments from scratch (Shane too, because every day seemed like the first time he’d ever picked a guitar up).

Punk Globe: There is a moment in your book I remember very good – you wrote that in some moment Spider and tried to learn to play the tin whistle. Did you spend a lot of time for your rehearsing at the very beginning or you learn the basics and progress in the process ?

James: Oh, I sort of answered this question already. We hadn’t much idea, technically, what we were doing. Shane had more of an idea, philosophically, what we were doing than I did. We all practiced really hard to make sense of the instruments we had and developed, I suppose, our own styles to suit both our personalities and the personality of the band, simultaneously.

Punk Globe: I always thought that The Pogues was a kind of provocation for British people. A kind of continuation of the traditions established by Sex Pistols in clearly a Irish attitude. What was the thing that shocked people the most: lyrical and musical motives or your artistic epotage?

James: Not sure what ‘epotage’ is. I looked it up. Seems like it’s a name that belongs to someone who follows their heart, even if it leads them into messy situations. That makes sense.

The Pogues I think provoked quite a range of different emotions in people, from the start. We were greeted by pure enthusiasm by our community – maybe a bit of puzzlement here and there. As things went on we were ridiculed by many for not being able to play, for being drunk, for being Irish (when most of us were not – well, yes, drunk a lot of the time, but when you mix drink with supposedly being, it’s taken as a pretext for some pretty shitty racism).

What shocked people the most, I’d imagine, was the way we went about things, not to mention the way Shane presented himself. I remember, a few years before, playing with him at The Jam’s Christmas party at a pub in Fulham. The guy who introduced the band (Shane, myself, Paul Well and Bruce Foxton) couldn’t restrain himself from commenting on what he thought was Shane’s ugliness, the size of his ears. It was repulsive to hear the introduction, and boring. He was probably drunk, but, shit, enough. I think more than a few people thought nothing more than gibberish was ever likely to come out of Shane’s mouth. What was a shock, I suppose, was that it wasn’t long before he proved everybody wrong. And the same went for us. They looked at us and assumed we were just shit.

Punk Globe: At the moment you are working on a TV show, exploring the music scene in the UK. Can you tell me, how it came about?

James: Well, not participating at the minute, but developing a TV show, which will follow me and a band on a narrow boat travelling from Liverpool to Hull on the British inland waterways, through Liverpool (obviously), Wigan, Manchester, Huddersfield, Castleford, Goole and to Hull (and, originally the idea was to reach the Greenwich Meridian at Cleethorpes on the Lincolnshire coast). The route will pass through my hometown and within six miles of where I went to school in Yorkshire.

The idea was born of my seafaring nature (so I like to tell myself – well, my ancestors were likely Vikings from the east coast of Norway, because Fearnley is a Norwegian fishing family name). The people in the United Kingdom are mad for the canals. There are two and a half thousand miles of inland waterway in the United Kingdom. Millions of people use the system. Millions live within a couple of miles of a canal. They’re littered with pubs and in the summer the pubs are rammed with people. So, I wanted to find stories along the route – such as the waterworks outside Liverpool, a couple of hundred yards from the canal, where John Lennon worked as a seventeen-year-old labourer in 1958. On the same day that he was sacked (as ‘unsuitable’) in the August of 1958, he bought a Hofner Commodore guitar from a shop called Hessy’s in Liverpool. I have invited John’s son, Julian, to come on the narrow boat that day and talk about his dad, play a song or two, perform in a pub. And that’s the idea along the route – Billy Bragg in Castleford to have a look at the outcome of the Miners’ Strike in 1984; Graham Gouldman and Eric Stewart to talk about Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, and about 10cc and Strawberry Studios in Stockport and Joy Division and Neil Sedaka (they’re all linked).

Punk Globe: After many years of touring with The Pogues you can see the evolution you made as an artists. How does it feel to be one of the fathers of celtic-punk?

James: The easy answer is – old. But, now, having seen what we accomplished over the years (well, mostly the formative years, as far as changing music in the way we did, which is why I concentrated on the years between our formation and our letting Shane go, in “Here Comes Everybody: The Story of the Pogues”), it’s a privilege to have made the contribution – if that’s what you call it – that we did, to the culture, to music, to people.

It’s great to see so many other bands who, in their way, seem to pay us homage. Not sure about the preponderance of overloaded electric guitars and chanting and fist-pumping. We never got into that (though there was an electric guitar or two). I always loved the picture of Shane (on the front of our box set ‘Just Look Them In The Eye….’, which shows Shane standing outside the Pindar of Wakefield with his hands in his pockets, staring out the photographer. That’s what I thought we looked like. I liked the idea we were a bunch of people suddenly appearing, to close off a street or something.

Punk Globe: But as far as I know you travel with the members of your own band – The Walker Roaders. Tell us how you came up with The Walker Roaders as your band's name? ?

James: Walker Road is a street near where I was brought up. They had a street gang who put fear into many a primary school kid. The street gang was called the Walker Roaders because they were from Walker Road. Their signature thing was to slice your thumbprint with a penknife if they felt like it.

Punk Globe: What are your future plans ? A world tour ? Or have you already had one ?

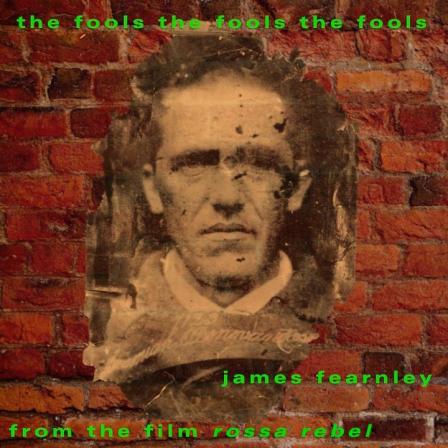

James: Well, we haven’t been on the road yet. We’re still in the studio. We’ve recorded a total of nine songs. It takes a long time this music making stuff. The band is made up of myself – singing and playing the accordion; Ted Hutt who used to be in Flogging Molly and plays guitar and produces (he’s a Grammy Award-winning producer); Marc Orrell who used to play guitar with Dropkick Murphys, but plays mandolin with us; Brad Wood, a producer of hundreds of records (Liz Phair, Pete Yorn, Smashing Pumpkins, etc.) who plays bass; Kieran Mulroney who sometimes plays fiddle and drummer Bryan Head who never stops working, on the road so much that we have to schedule our recording sessions for when he’s in Los Angeles.

Punk Globe: Can you say that being a part of this new band is the most unusual thing you have ever did ?

James: Playing in the Walker Roaders is the most unusual thing I ever did? Musically, you mean? No. I once climbed down a pole in North London, into a dingy basement, to do an audition for a room full of Goths in looped pullovers.

The band before Walker Roaders was Cranky George. That got a bit unusual. At one time the band was just me and Dermot and Kieran Mulroney. Dermot is the actor in My Best Friend’s Wedding and Young Guns. Dermot plays cello. Kieran, as I’ve said, plays fiddle. We performed The Mariner’s Revenge Song by the Decemberists. I knew the chords and read the lyrics. Neither Dermot nor Kieran knew the song, so their backing vocals were the sounds of men pulling ropes as if on a ship.

Punk Globe: There is an opinion that every musician playing a song gives it a certain feel You play a lot of different songs with The Walker Roaders. So according to your opinion, what things do you, as an authentic artist, bring in all these songs ?

James: Not just in the Walker Roaders, but in Cranky George and before that the Low and Sweet Orchestra (with Zander Schloss, Mike Martt, Tom Barta, Dermot and Kieran Mulroney and Will Hughes) and before that (and after that too) with the Pogues – what I wanted to do was offer up a bit of hilarity in the fast songs, pure but understated emotion in the slow ones, the sound of a sense of justice, I suppose, in the angry songs. Whatever – whatever – the ‘justice’ thing sounds pompous. I don’t mean to be pompous. What I can’t stand is watching people enjoying too much what they play. It’s not for the player. The enjoyment, the emotions, are for the audience. The bands I’ve been in have been delivery systems, catalysts, I suppose. I hate to see musicians enjoying what they do, how good they are. It’s like laughing because you know the fucking punchline of a joke.

Punk Globe: You’ve been a part of many different projects - starting from Low and Sweet Orchestra and ending with your activity with Cranky George. I’d like to ask you about your last LP. Listening to it, I thought that you, as a band, broke from classical tradition of celtic-punk. So did you want to record a calmer and more lyrical album?

James: You mean the Cranky George record, “Fat Lot of Good”? Most of the songs were written by Kieran. I wrote maybe four of them – one of them I suppose in the ‘classical tradition’ of celtic-punk (‘Greenland’s Ice’). Dermot wrote one. Kieran, Dermot and I were neighbours once, a while ago. What sound we stumbled upon came from jamming in Dermot’s garage with cello, violin and accordion. So, I guess it was calmer because of the instrumentation. When we added lyrics, I don’t know – Kieran’s a writer by trade. I’m a writer by pretension. After our work with the Low and Sweet Orchestra (where we were regarded as the ‘colour’), the Cranky George sound was the one we ended up with – wordy lyrics, lavish arrangements, maybe. We worked on the record as a band for years, let it rest for a bit, and then took it up again to finish it.

Punk Globe: But how hard it was for you to get a common language with all these people ? As playing celtic-punk you must take into account some soft traditions of celtic music with punk and hardcore energy and rage. So how did you find a balance between the people and the tunes ?

James: Zander Schloss and Mike Martt came from an LA punk background (Tex and the Horseheads, Circle Jerks). Zander was Joe Strummer’s guitar player for a long time. Kieran and Dermot and my sound came from – I don’t know: both guys were part of a family quintet of sibling string players and were classically trained. Both are fantastic singers. Kieran was in a barbershop quartet at college. As brothers they had a relationship I could only stand back and admire, when it came to music. So, the combination of punk has-beens and sibling cello and violin players was fairly original I’d say. I tacked a course in between.

Punk Globe: There is an opinion that the more energy in the composition\song, the more dynamic it is. And talking in general I can say that it’s true. But The Pogues had lots of lyrical and almost ballad-like compositions with strong and catchy dynamics. Like “Lullaby to London”, “Fairytale to New York”, and lots of others. What’s the secret,on how make your listeners feel what you feel ?

James: Well, that equation makes sense on the face of it. The secret to making one’s listeners feel what we feel is I suppose ‘giving out’ I suppose – generosity, brazenness, audaciousness and a bit of pretension (the French regard ‘prétension’ as a positive quality).