The first thing that hit you was the sound, that simple beat of a drum and a girl’s voice. Boom-pomp bomb-bomb. Boom-pomp bomb-bomb. “I saw you standing on the corner…”

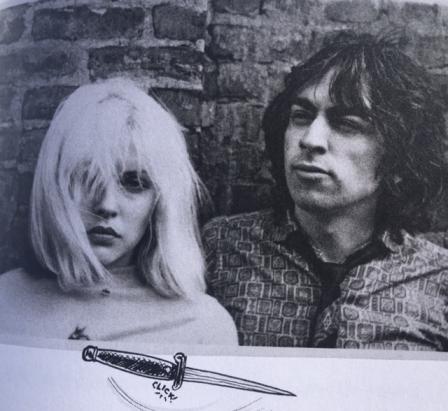

Debbie in black and white. Photo by Bob Gruen.

It was Ronettes-like, but it wasn’t. It sounded like the Shangi-Las, but it wasn’t them either. It was sweet and it was fun and it was rolled out in a layer of lyrical danger that documented jealousy and pain and the destruction of the human race in a neighborhood of gang fights, sex offenders and rifle shots. “Come on, rip her to shreds.” What. The. Fuck.

They called themselves Blondie and navigated a path down a smutty Bowery reeking of power chords, intellectual rhythms and absinthian poetics to carve their own turf. Forty-something years later, lead singer Debbie Harry has issued her memoir.

“Face It,” published by Dey Street, contains a slew of salacious bits likely to shock those who first discovered Harry alongside Mulch and his fellow Muppets on American daytime TV: Here is David Bowie whipping out his diamond dog after a coke-fueled caucus with Iggy; There, is Harry’s dabbles with dope and her clubland forages dating back to the hippie-trippy ‘60s and extending right on through the trash-and-glamour days of the New York Dolls. “I had a big crush on David Johansen,” she confesses. “I made it with him once.”

Her story begins, well, at the beginning. Born Angela Trimble on July 1, 1945 and promptly put up for adoption. Taken in by The Harrys of Paterson, New Jersey, Angela was given her new name: Deborah.

Debbie on drums: “Trying to keep time at the Mudd Club.” Photo by Allan Tannenbaum.

“At three months, I’d already lived with two different mothers in two different houses, under two different names,” she writes. “Thinking about it now, I was probably in an extreme state of panic. The world was not a safe place and I should keep my eyes wide open.” Abandonment issues would plague her all through her life. “That feeling never really went away.”

Growing up in the shadow of Manhattan, she recalls the gleaming lights of the big city beckoning her at a young age, sprinkled with Christmastime visits to Rockefeller Center, childhood luncheons at Schrafft’s and kid-friendly shows at Radio City Music Hall. “It was magical…an enchanted forest teeming with people and noise and tall buildings.”

At the age of 20 in the mid-1960s, Harry would finally make it to Manhattan on her own. She secured a four-room apartment on St. Marks Place for $67 per month. The Velvet Underground – “wild and beautiful with a set designed by Andy Warhol” – staged an extended engagement on her block. Janis Joplin performed at the theater around the corner. “Her whole body was in the song,” Harry says. “I’d never seen anything like her onstage.”

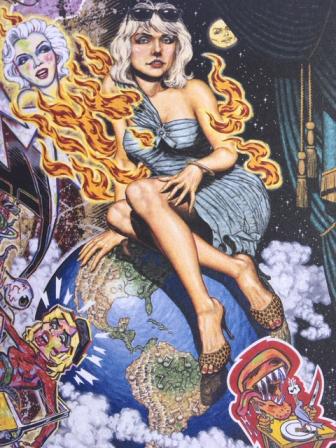

Painting by Robert Williams.

She sold posters and bongs at a neighborhood head shop, waited tables at Max’s Kansas City – “I served dinner to Jefferson Airplane two days before they left for Woodstock” – and performed with an ever-expanding group of musicians who called themselves Wind in the Willows. “My first time on a record. I sang lead on one song, but aside from that I was like wallpaper, something pretty to stand in the back in my hippie clothes.” Harry was garnering attention, but it wasn’t always the favorable kind. More than one day was spent evading a house painter from New Jersey who had gone to stalking her. The memory would a decade later inspire the Blondie song, “One Way or Another (I'm gonna get ya, get ya, get ya, get ya).”

She headed west hoping for a new start, but the relocation was brief. “I could not live in L.A. in the sixties, for fear of losing my soul,” she says. “Instead I came back to NYC and became a Playboy bunny and junkie. Go figure.”

The impression one gets of Harry in the early ‘70s is of a talented person searching for something but lacking a map of how to get there. She is blessed however with an innate belief that fate‘s shadows bend the realities to the angles where they are meant to be. “Drawn together as if by some extra-earthly magnetic force…things that connect and become woven and then shoot off to form previously unimagined combinations. Small changes that tumble into a fresh dynamic – as coincidence and chaos give birth to a new creation. Coincidence: the divine intervener…”

For Harry, the fortuitous location where coincidence met chaos was the Mercer Arts Center. The divine intervener was the New York Dolls. The Mercer Arts Center a “labyrinthian place with lots of different rooms” staged performances from 1971-1973 by Eric Emerson and the Magic Tramps (whose roadie and occasional bass player was Chris Stein), Patti Smith (still doing poetry at that point), as well as the Dolls.

“They were ragged and raunchy and uninhibited, strutting, swaggering about in their tutus, leatherette, lipstick and high heels,” she notes of her nights spent escaping into the freedom promised by the music. “I figured what attracted me so much to their shows was that I wanted to be just like them. I just didn’t know exactly how to get it rolling.”

The Mercer disintegrated in the August 1973 collapse of the Broadway Central Hotel which housed it. A few months after its destruction Hilly Krystal would offer a new place on the Bowery – which he named CBGB – to bands looking for a place to play. Harry meanwhile connected with Elda Gentile to join forces as the Stilletoes. The band featured a rotating group of musicians, one of whom was Chris Stein. Harry and Stein would eventually break off and start their own band to perform at Max’s Kansas City and Club 82 and opening for Television and The Ramones at CBGB’s. Blondie was born and Harry and Stein forged a relationship – first as a couple and today still as friends, that would last a lifetime.

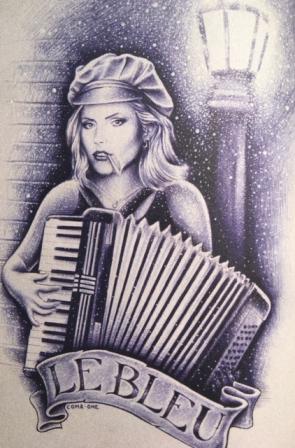

“Le Bleu,” unspecified fan art.

“CBGB’s has become a legend, but in those days it was a dive bar on the ground floor of one of the many flophouses that lined the avenue,” Harry says, running down a list of memories that includes derelict stores, a back alley full of rats and rubbish and shards of broken glass, and the club itself with “its own special reek – a pungent compound of stale beer, cigarette smoke, dog shit, and body odor.”

They got paid in beers and sold pot to make the rent. “We felt that we were bohemians and performance artists, avant-garde. And when you add to the mix this very New York DIY street-rock attitude that we had, you got punk,” she writes.

Blondie’s debut album was released in February 1977 and the band hit the road for the first time, landing in Los Angeles where Rodney Bingenheimer gave them airtime on KROQ, Jeffrey Lee Pierce – later of Gun Club – initiated a Blondie Fan Club, and an engagement at The Whisky had them sharing the stage with Tom Petty, and The Ramones, as people like Joan Jett, Ray Manzarek, and Phil Spector stopped by to check them out. Then it was onto the bigger stage - supporting Iggy’s shows with Bowie, touring Europe, and embarking on a five-year odyssey that saw them getting sucked into the hectic ride inside of a caged treadmill that is corporate production.

Debbie and Chris. Photo courtesy of Debbie Harry’s personal collection; illustration by Sean Pryor.

“I didn’t choose to be an artist to have other people tell me how to create. We felt a deep need for creative freedom, a day-to-day rattling away on the bars of our emotional cages,” Harry writes. “I would be onstage and there’d be 5,000 people pulsing their desire at me. You could feel the heat of it. The raw animal physicality…but looking back, I think my ego had run amok. I was just part of the game, a cog in the machine. I mean, you can pretty much sell anything when the corporate structure gets behind it and turns art into commerce.”

Blondie’s best days, Harry figures, were the early ones: “struggling artists, scuttling around the Lower East Side just trying to get something going…success, when it finally came, quickly started to feel almost anticlimactic.”

Less than 20 pages – essentially one chapter - covers the band’s run from the time of their debut album release to their first American single landing at number one in 1979. It was a volatile two years, but with Harry’s unique perspective of the time, you wish she spent more time in the book there. Overall, there are many quick, one-hit references that beg for longer exploration. Perhaps the method of documentation – an oral memoir in collaboration, with longtime music journalist Sylvie Simmons – has something to do with that. The act of writing things out generally seems to bring with it more detail.

Still, Harry is upfront about her human insecurities, from childhood to beyond, and there are episodes of compassion – her bond with Stein, particularly after he was diagnosed with a rare and complex disorder is one - as well as other incidents almost too painful to comprehend. The 352-page oral memoir features dozens of pieces of reproduced fan art – illustrated likenesses of Debbie sketched by the hands of her fans from across the globe - as well as some of her personal childhood photos, band images and portraits of Harry nightclubbing it through the decades.

“How do we edit our life into a decent story? That’s the rub with an autobiography or memoir. What to reveal and what to keep hidden?” she asks introspectively in “Face It.” “I have had one fuck of an interesting life and I plan to go on having one.”

Chris and Debbie, the closing of CBGB’s. Photo by Bob Gruen.