Chances are if you ventured into downtown Manhattan during the flourishing art and music scene of downtown New York that was the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Brooke Delarco had a big influence on how you heard things.

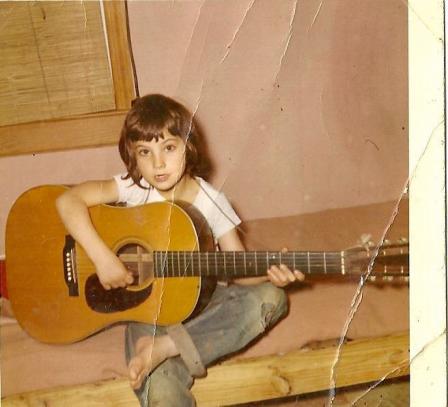

Punk Globe: Where you inspired by music at a young age?

Brooke: I came from a musical family. My mother was an early pioneer in folk music. She was initially slated to be the singer in The Weavers, but she was like 18 and then I came along. That was scandalous, ha ha, but, she never really held that against me. Ronnie Gilbert became their singer. My mother continued on in the folk music business and stayed friends with Pete Seeger, putting on folk festivals and doing things with him. So, I was around music all the time.

Punk Globe: Where are you from originally?

Brooke: I was born in Nyack, New York, and grew up in Woodstock. I lived in Wilmington, Delaware - down the road from Tom Verlaine, although I didn’t know it at the time. We moved when I was 14 to Atlanta, where my mother was really active in the Civil Rights movement and the folk music scene. That’s where I got more into music. It was the late sixties.

Punk Globe: How did you get into the sound business?

Brooke: I played around on guitar, but I knew I would never be a great player. I had a boyfriend who was in the Hampton Grease Band – have you ever heard of Bruce Hampton? Along with guitar player, Harold Kelling, who was really the guy behind them, they were responsible for setting off the whole southern rock scene that came out of Atlanta. They were like the psychedelic equivalent of the New York Dolls, in that they were groundbreaking, a blend of Television meets Captain Beefheart. He left the band in ‘71, started another band and that’s when I connected with him, brought along a tape recorder and really started getting into a lot of recording.

After kicking around art school for a couple of years, I left Atlanta and came back up to New York. This was in ’75, and that’s when I got a job at Vanguard Records through another boyfriend who was chief engineer there.

Punk Globe: Terry Ork founded his D.I.Y. Ork Records label in 1975 and released Television’s debut single “Little Johnny Jewel,” as well as subsequent records by Richard Hell, Alex Chilton and others. How did you meet up with Ork?

Brooke: A friend of mine, Mark Abel, was mixing sound for Television and the Talking Heads. He brought me down to CBGB’s to see Television and introduced me to Terry.

That’s when I hooked up with Feelies. They started playing around a lot and needed a sound mixer. That led to me going up to Trod Nossel to do a Feelies 3 song EP for Ork Records which was subsequently never released. However, because of that, I started to develop a relationship with Terry. He began calling me in for projects he had going on, like the Richard Lloyd single, Chris Stamey, and Lester Bangs as well.

From then on, I continued to mix The Feelies’ live sound and do their recordings. I did a set of demos with them which eventually became 2 of the tracks on the Ork compilation that Numero put out. One of the original recordings from Trod Nossel, Fa Ce’ La was also included, as well a live cut from CBGB’s. (The multi-disc box set, “Ork Records: New York, New York” was released October 2015). This was over the course of three years and the band had changed. We went up to Woodstock, after Anton Fier joined, to Grog Kill studios to record the songs that became the demo that got them signed to Stiff Records. Those recordings also became the Rough Trade single "Fe Ca La" / “Raised Eyebrows.” Because of my connections at Vanguard (Studios), we booked them in there to do “Crazy Rhythms.” I left in the middle of those sessions due to a difference of opinion on recording techniques with the “producer” who subsequently quit 2 weeks later. The boys were then on their own, which is why the recording is so stripped down and somewhat sterile, since they didn’t know how to get the sounds that I had given them.

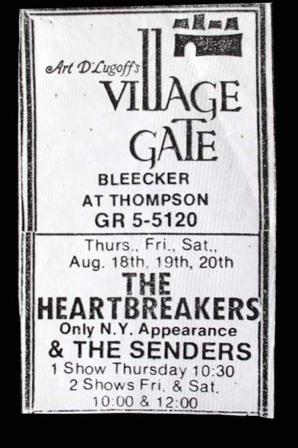

Punk Globe: You worked the Heartbreakers shows when they returned to New York in August 1977 for a three-night stand at the Village Gate?

Brooke: Terry Ork was putting on a series of shows at the Village Gate, so again he brought me in to do sound. I had never even heard The Heartbreakers before the Village Gate. The record wasn’t out yet and they’d been in England for most of the time in ’76, so that was the first night I heard them.

Punk Globe: The New York Times review by John Rockwell is pretty funny, and reads this way: “Not to be confused with Torn (sic) Petty and the Heartbreakers, the Heartbreakers are a punk‐rock quartet that grew out of the original New York Dolls… their current three‐night engagement at the Village Gate on Bleecker Street—which has now turned over its basement room to the punks—constitutes something of a homecoming, and the local punk scene and scene makers were out in force…” You worked the sound the first night and the last set on the third night.

Brooke: I did all 3 nights. The first night which was one set and the last set of the third night became the Live at The Village Gate release. You listen to the first night and they were really on it. Then you listen to the second night, and it’s like... slowed down. You knew they were back in New York and speed was no longer a factor, haha.

I guess they liked my sound. Billy (Rath) was the main advocate and after I did those shows with them, they wanted me to do the Max’s (Kansas City) shows – so I did those series of Max’s shows up until probably late summer of ’79.

Punk Globe: You did the live mix for the Heartbreakers “Live at Max’s” album in late ’78 which had Ty Styx playing drums, as Jerry Nolan was on-and-off with the band by that point. To your ears, was there a big difference when Jerry was there?

Brooke: Oh yeah; Jerry had a lot of swing. I came from a jazz background as well as my rock roots. I was into Miles Davis and Coltrane, Elvin Jones as a drummer, so I had a certain approach to recording, especially drums, that was based on listening to guys like Elvin and Tony Williams. I think Jerry liked my sound because he was based in the whole Gene Krupa connection.

Punk Globe: All these decades later, you have maintained an interaction of kinds with Johnny Thunders – being among other things the Facebook administrator for “LAMF! Lets’ All Make Friends,” and “Johnny Thunders Came Back To Kick Ass Again.”

Brooke: Yeah, I still sort of have a connection with Johnny. Working with him in the past, Johnny was never anything short of a gentleman and nice to me. Same with Jerry, they were totally professional and supportive with any of the shows I did with them. Of course, there was the one time Johnny scammed me on a dope deal, but he had the sweetest smile on his face. Sadly, it was the last time I saw him.

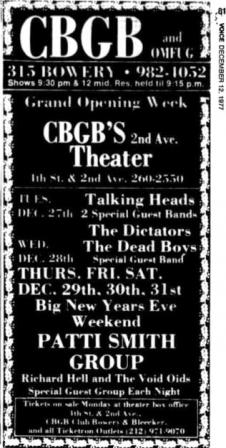

Punk Globe: The late 1970’s was a busy time. You were also working with Patti?

Brooke: I think the first show I did with her was at the Elgin Theater (July 1977). I was friends with (PSG drummer) Jay Dee (Daugherty) and he pushed for me to do their sound. CBGB’s - I did the Second Avenue Theater nights w/ Springsteen and New Year’s Eve (Dec. 29-31, 1977). Then we went to Akron, the Agora, Cleveland, Buffalo and I went over to Europe and did half the tour with them - up until they left me stranded at the Wall in Berlin! Patti did it.She thought I was too friendly with Jay Dee and the drums were too loud. But I’ve got no issues with Patti. I’ve seen her since then.In a certain way we are cut from the same cloth.

Punk Globe: You built the sound system for the Mudd Club?

Brooke: Yes, I designed and installed the sound system at the Mudd Club. Steve Maas was friends with Brian Eno and one night Steve was talking to him: “You know I’m opening this club, what do I need?” So, Brian drew him a little schematic on a napkin of a basic sound system, you know, with the little triangles that show the amplifiers, and a board, and little lines to the speakers and stuff like that. So, Steve knew I was doing sound for all these bands and he asked me to design and install the sound system. I spec-ed it out, designed it, wired it all up and installed it. We had a good budget, but we could only afford like a half-stack of speakers - and we got a good board. Later, when people would ask him about the sound system, he would go: Oh, Brian Eno designed it. Well, you know, Brian Eno is a more popular name than mine is, haha.

Punk Globe: You turned Blondie down?

Brooke: Yeah…

Well, here’s the story on that one: I was mixing sound for the B-52’s at the Mudd Club. It was the night Robert Fripp and David Bowie were there and I heard Chris and Debbie were there and their conversation was: Wow, I wonder if we can sound that good. Anyway, a few days later Chris asked me if I wanted to do sound for them. I was tied up with Patti and the Feelies and The Heartbreakers. I didn’t think I could take it on. I hate to say it, but they were kind of poppy, and I didn’t think they were going to take off. So yeah, unfortunately, I turned them down. I always joke about it; It was the biggest mistake of my career. That was also the night Fripp told the B’s they should take me into the studio with them. They didn’t.

Punk Globe: You’ve done both live work and studio work. Do you prefer one over the other? Does your approach to the setting vary?

Brooke: I am mainly a studio mixer. And that’s one of the approaches I brought to those bands (live). I gave them more of a studio vibe mix and characterize each band in their own sound, rather than the typical live sound/club application with the same sort of sound for everyone. So, I was able to get hired by those bands because I gave them their own unique sound. A number of those bands got signed because of my shows with them.

Punk Globe: What did you do in the aftermath of that busy time in New York in the 1970s and ‘80s?

Brooke: I dropped out of the NY scene in’81, too much junkie business! I left New York in ’89 or ’90 and moved to Washington D.C. where I worked at Inner Ear Studio - which was the home of Fugazi and for a lot of the bands down there. I worked exclusively on records, producing and things like that.

Punk Globe: What are you doing/working on these days that’ll see the light of day in the future?

Brooke: I’m trying to get a few of these recordings that I have of The Feelies and Patti Smith and a couple of others picked up and released by certain labels. There is also a video of a live Heartbreakers show at Max’s from ’79. I’m working on getting that released on DVD.

What I can envision is a Lenny Kaye Nuggets-type thing with bands I’ve recorded and trying to get that out as a historical representation of what was going on at that time. But it’s hard to bring people to the table.

Punk Globe: If you could choose a fantasy search for a particular set of recorded tapes, what would they be?

Brooke: I would be on a mission for the Heartbreakers (“L.A.M.F.”) tapes that Leee Black Childers (allegedly) took from the Track Records offices.

There’s a story that there are some masters - when the Heartbreakers starting having issues with Track and remixing and remixing and things started falling apart – supposedly Leee, or someone else for him, broke into the Track offices and they stole the Heartbreakers multi- tracks.

The mixed masters obviously Jungle (Records) because they were able to remaster them and do that re-issue, which sounded good. The mastering to vinyl was not good, that’s why it sounded muddy when it came out. But supposedly there are these multi-tracks - the original two-inch tapes, before they were mixed. I’m not sure if those are the ones that became L.A.M.F. or whether they are some other recordings, but if I could lay my hands on them ...