| |||||

|

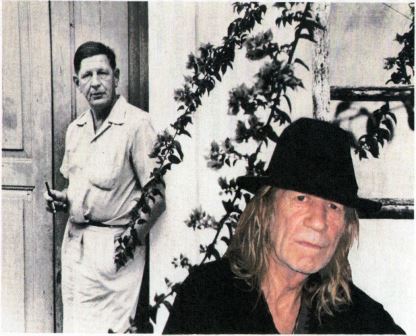

Penny Rimbaud is someone who Iíd been dying to talk with since I first heard Crass when I

was twelve. This interview shows what a dynamic and humble person Penny can be. We talk

about poetry, politics, music, meditation, and of course, bread. His work transcends punk

and reaches toward the human core of artistic expression. He was an absolute joy to

interview. Hope you enjoy the read!

|

Penny Rimbaud: Iíve spent most of today rebuilding the chicken run because weíve got

foxes in the area and going over some poems of Wilfred Owen which Iíll be doing a recital

of later in the year. Thatís all Iíve been doing, reading, writing, and meditating. The

best news about the house is that weíve almost paid off everything that we owed on it for

the better part of ten years and weíre now about to start the process of setting up a

trust so that we can turn it into a state institution for the radical arts. Itíll be held

as close as it can be to perpetuity and hopefully have a long life beyond that of the

three current residents as a center for activism and the arts.

Punk Globe: In the beginning, did you have any misgivings about Dial House becoming a

state institution?

Penny Rimbaud: No, not at all. We live in the state, like it or not. If I can oblige the

state to take on an institution of learning, peace, wisdom, and joy, Iím pleased to do

that. Weíre not going to change the state by standing outside of it and shaking our

fists. Weíre going to change it through our profound belief in kindness. Itís about using

the power of the state to make it change itself. Weíre all responsible; thereís no point

in wagging fingers and blaming others. What can you do thatís practical and helps others

as well as yourself? Iíve spent fifty years trying to demonstrate my way of doing that,

and if that becomes part of the body of the state, fantastic. Bit by bit, thatís how itís

all changing.

Penny Rimbaud: No, I donít do much work with activists over there. Itís my few days off a

year where I wander around, sit in cafťs, and maybe write down a note on a napkin here or

there. Last year, we got involved with a group of anarchist printers and I did a reading

using the printing presses as backing music. My mind is always working on stuff, but I

consider that my time off.

Punk Globe: What do you think are the biggest benefits of taking time off?

Penny Rimbaud: You get a perspective. I think that one can become very dug-in on oneís

own domain. My domain happens to be England, itís just Dial House, but all of Britain.

Being out of oneís own culture is always valuable. I can understand a small amount of

Spanish, but I donít understand the whole social set-up. If Iím in England, I can read

every face and every action and understand whatís going on. Being outside of that helps

me be a freer person for a while. I can also take stock of things and look at what Iím

doing in life from a distance. There are a few things that are constant in my life and

thatís my great faith in life, my love of and devotion to life, and my view of death as

an exact mirror of life. I carry that with me wherever I go. The day-to-day things of the

material world can sometimes be seen better if youíre not living in the middle of it.

Having the time to assess whatís important makes practical decisions easier because

youíre not actually weighed down with all of it.

Punk Globe: Have you made any effort to make Dial House accessible to travelers?

Penny Rimbaud: Not really. As a human experiment about fifty years ago, I removed the

locks of the door. Iím still seeing whatís happening. Iím not advertising it or trying to

get anything from it, Iím allowing it to make its own demands in its own way. I made that

decision and Iíve stuck to it faithfully. It wouldnít be in my nature put out ads, people

find their own way here in large numbers. I can share time or not share time with them.

Itís not a social center in that sense. Iím working all the time, whether itís writing

poetry or making bread. Thereís no difference between work and play. I decided fifty

years ago to be here now.

Punk Globe: A lot of what youíre saying reminds me of Alan Watts, can you speak to his

influence at all?

Penny Rimbaud: Yeah, I first started reading Watts when I was 18. It inspired me greatly:

I donít think influence is quite the right word. His work, the Beat poets, and what was

happening in the Ď60s in the West End of London all really inspired me. It was the whole

DIY essence of all of that, especially Gary Snyderís work, which struck a chord with me.

The finding of oneself within nature was very inspiring to me. It was a new attitude;

they were showing us a different way to live.

Punk Globe: Have you crossed paths with Gary Snyder at all?

Penny Rimbaud: Not Snyder, no. I did a reading last year at City Lights bookshop and

Ferlinghetti was going to come, but heís an old guy now and he wasnít well. If Iíd been

on the West Coast for a bit longer, I would have tried to make contact with Snyder, but I

was flying in, doing the reading, and flying out. I canít afford to do otherwise.

Punk Globe: How do you approach revising your poems?

Penny Rimbaud: Iím never deliberate. An idea or vision appears and I translate that into

words. I donít depend upon my reasoning intellect to write; itís a much more intuitive

process. I might get up in the morning and think Iím going to write a poem, but Iíll sit

at my desk, and ten minutes later, Iíll be off chopping wood or feeding chickens. I donít

feel thereís any difference. Thereís youíre doing when youíre writing poetry that youíre

not doing when youíre making bread. The poetry comes from something deeper that wants to

express itself and ask its own questions. I always start in a notebook with a pen or a

pencil. When Iím happy with that, I type it up. There I might play with the shape or the

aesthetic of the poem. Change a line break, add in a rhyming line, and get it solid. Iím

not bothered about whether itís good or bad, but about whether itís true to what I feel.

Punk Globe: What was the process like for the poem, ďOh, AmericaĒ specifically?

Penny Rimbaud: I wrote ďOh, AmericaĒ right when I had the idea. It happened and came out.

Gee had this gig showing one of her films at a prestigious concert hall in London and she

asked me to do something and this poem suddenly came to me. I wrote that subconsciously

to fit to a piece of music which is often used at military marches in America. When I

realized that, I thought it was the right music to use in a criticism of the American

state. I write out of the same necessities that I make bread out of. I make bread because

I need to eat, which feeds my stomach. I write poetry because it feeds my heart and soul.

Punk Globe: Thatís really beautiful. Did you have the same philosophy when you were

drumming in Crass?

Penny Rimbaud: Very much so. It was expressed in a different way. It was just Steve and

me for the first six months or so. Steveís got a different take on the world from the one

I have. In a way, I translated my feelings into his energy. I come from a privileged

background. From that, I knew things could be better and more equal. Iíve used the

education Iíve been given to try and undermine the upper class. ďActs of Love,Ē which I

did in the last year of Crass carried very much the same philosophy that I continue to

express in different words. I wrote ďItís You Who Makes The World Go ĎRound,Ē in the late

í60s, which was the same idea as ďThere Is No Authority But Yourself,Ē inspired by Alan

Watts, as you pointed out and by George Harrison. Everything I did in Crass was inspired

by the idea of ďbe exactly who you want to be,Ē which we put into the song ďBig A, Little

A,Ē a practice of helping people to think about a world that they might like to see, to

show them that they had the power to change a world where theyíd been told they hadnít.

One of the things I picked up from Alan Watts and that perspective on Eastern philosophy

was the practice of karmic yoga, a yoga of service which shows that thereís no greater

entity to help you but yourself. That devotion, that service is part of what keeps me

going.

Punk Globe: When you mentioned George Harrison, I thought of the Beatles art contest that

you won in the early sixties. Did you get to talk to him at all?

Penny Rimbaud: I was meant to go to dinner after the show with the group, but I just

wanted to get back to my mates at art school. Iíd spent all day in the studios and it was

really busy because The Beatles were beginning to become the absolutely massive band that

they became. The whole show was a very over-excited, rowdy business. I was going to get

the records signed and all that, but I thought, ďAh, fuck it. I want to get back to my

friends.Ē I laughed it off. Iíd gone off The Beatles by then because I thought they were

too commercial, but my younger sister was a member of the fan club. I entered that

contest with the idea that I was going to win. I donít know where I got that idea,

because there were thousands of entries. Iíd invited my sister to come up and meet them,

but she couldnít because she was at convent school. She was doing a choir performance

that night. The chief nun in the convent arranged for the entire choir to watch the event

on television before they performed.

Punk Globe: How and when did you first come up with that archetype of the Glaswegian

fourteen year old that Iíve heard you refer to?

Penny Rimbaud: During Crass, we were traveling around the U.K. Weíd given up touring

abroad because we thought people werenít understanding what we were on about. They were

treating us too much like a rock band. Dial House is fairly close to London and this

whole area is very affluent. There is poverty here, but very little of it. The further

you go north in Britain, the more poverty youíll see. In Glasgow, it was extreme. Itís

one of the poorest cities in Britain. We played several gigs in Glasgow and there was

this group of fourteen year old kids whoíd spiked up their hair to make it look punky.

They were really sweet and they all wanted to meet Eve. They rushed over to her and

immediately connected. When I saw that, I thought, ďThis is why weíre doing this.Ē Before

I made a decision, Iíd keep myself in check by asking myself if those kids would do the

same. We were being offered these big record deals. If we had wanted to, we could have

signed with any label. We could have done gigs in massive theaters. We were turning that

down all the time. People would ring up and ask why we didnít play in their area. Weíd

tell them, ďYou arrange it and weíll come do it.Ē We would only play in workingmenís

clubs or youth clubs. Occasionally, weíd play a pub or a small theater. Our gigs were

small, that way it wasnít intimidating. Kids in Glasgow might be intimidated by a big

theater with stage lights and bouncers. It was a way of breaking that whole rock star

mentality and not getting carried away with the possibilities.

Penny Rimbaud: There wasnít any temptation at all. There was always a possibility that

weíd get carried away in our own sense of power. When a following grows up around you,

itís not difficult to misuse it. We were planning a massive march, which might have

gathered together several thousand people in protest of nuclear proliferation. We were

going to go from north to south and stop at each of the nuclear installations in Britain

and end up in London. We, as a band, could have gotten in our van and fucked off if

things got too dangerous. If youíre planning something that large and creating huge

bodies of people, you need to be responsible for each oneís safety and well-being. We saw

that it could create some really messy conflict, so we scrapped it. This was following

the city riots which we had been involved in. Those didnít lead to too many arrests, so

we thought we might be able to plan something bigger. Again, it comes back to the

fourteen year old Glaswegians and what theyíd be able to do.

Punk Globe: Do you have other ways besides the fourteen year old Glaswegians of checking

yourself?

Penny Rimbaud: For the past few years, Iíve been trying to balance how much I do for

myself and others. The lily grows and gives its perfume, but itís not aware that itís

giving off such pleasure. I ask myself if I was after something after I do it. When I

analyze it and find self-interest in it, I say ďOkay, Penny, learn the lesson.Ē Itís like

programming a computer. If you hit the right buttons in the human brain, you can rewire

yourself. Itís hard work. Itís easy for me to say this kind of thing because I donít get

on the subway every day and see all the adverts and interact with all the people. Iím not

watching television or reading the newspapers or doing any of the things that could

distort my sense of beauty.

Penny Rimbaud: Anger can be beautiful if itís righteous. Youíve got to be really

conscious of how youíre using it in a particular situation or dialog. When I was caring

for my dying mother, the only way I could get her to respond was to slap her in the face.

She was suffering from brain cancer. She was tearing at herself in these explosive fits

of rage and tears. I only did it once and I hated myself for doing it, but it stopped her

from hurting herself more. Did I do it because I was pissed off? I think so on some

level. When she became overpowered by her rage, she got potentially dangerous to herself

and to me. If itís not malicious, it can sometimes be kind to express anger. It can be a

useful tool, but it needs to be used sparingly.

Punk Globe: Did righteous anger play into some of your work with Crass?

Penny Rimbaud: Of course, thatís an aspect of it. Personally, I was never afraid of

nuclear war. If it happened, it happened. I think people become so easily intimidated and

lose their joy of life too quickly. I used the nuclear bomb as a metaphor to say, ďLook,

this is how you might imagine it, but what are you gonna do about it?Ē As I explained

earlier, my relationship with Steve enabled to me to phrase that in a kind of street

language that could help me get through to my target audience. When I was a kid, I was

listening to blues records and I could see that the people who made those records were

coming from a very earnest place and playing what they felt.

Punk Globe: Allen Ginsberg called that ďstreet language,Ē kitchen talk. Would you agree

with that?

Penny Rimbaud: Yeah, I think so. It wouldnít be the talk in my kitchen, I like to be

alone and in my own space when I cook. There was an arts movement called the kitchen sink

artist and their work was very gritty and harsh with a working class ethic.

Punk Globe: Are you still in touch with Steve? Whatís your relationship like with him

now?

Penny Rimbaud: Eve and I decided weíd go to his last gig he played with his band. I see

him every so often, maybe six or seven times a year. Weíve got different interests, but

we still love each other a lot. We donít have a great deal to say, but we always reaffirm

our love and respect for each other.

Punk Globe: Do you see Sid and Zillah from Rubella Ballet often?

Penny Rimbaud: Sidís been really ill, so they havenít come over recently, but they come

over when they can. Sid took the same route I did in treating his cancer with homeopathic

medicine.

Punk Globe: My favorite Crass album ďPenis Envy,Ē is a piece IĎve wanted to ask you about.

How did that come about?

Penny Rimbaud: It started when Crass was being viewed as a boot band. All-male,

aggressive, and masculine. The women in the group had always been a huge part of what we

were about and they seem to be getting the short end of the stick. So, we went ahead and

made a feminist album. The music was slightly different because it was centered on

womenís voices. We were saying very different things. It was very radical at a time when

that sort of message didnít find its way onto vinyl. It was powerful feminist statement.

The only other band that anywhere near matched it were Poison Girls, who were a very

powerful feminist outfit.

Penny Rimbaud: Make bread. I went on a silent retreat thinking I was going to get

instruction about meditation and learn all sorts of things. I turn up and the head of the

retreat told us we were going to sit. I thought, ďOkay, what else are we going to do?Ē

That was it, that was the whole instruction. After that, we sat, looked at a wall, and

there was no one telling me what to do, say, or think. We got what was called a Dharma

talk every day and Iíll say what he said to me. Just sit. Allow yourself to get out of

the way of yourself. Spread that joy of life.

|

|

|