| |||||

|

|

“When they (Ramones) returned from the first UK dates, they played in Youngstown, Ohio, and didn’t draw many people. (Ramones’ manager) Danny Fields turned to me and said, ‘If you can get the money from the club owner, you can be the tour manager.’ So I went and got the money, no problem, and it was official. I had become a tour manager. Little did I know I would do it for the next quarter of a century!” said Ramones tour manager Monte A. Melnick. “It’s been a long road since the evening of August 6, 1996, when the Ramones, New York’s premier punk band and Rock’ n’ Roll Hall of Famers, walked off stage for the last time. No hugs. No goodbyes. No nothing.”

Over twenty years and 2,263 live shows, Monte now is the Audio/Visual Supervisor at New York Hall of Science. The fifth Ramone, Monte chronicles with Frank Meyer of Esquire TV, POPsmear magazine, contributor to Vanity Fair, Variety, New York Times and LA Weekly, front man for The Streetwalkin’ Cheetahs and Sweet Justice the history of the undeniable pioneers of punk rock.

But Monte’s story starts long before NYC’s decay from a mass-exit to suburbia. The late Tommy Ramone said of Monte in the forward of On The Road with the Ramones, “I bumped into him while riding my bike around Forest Hills High School.”

Monte says, “I was more into sports, but Tommy was into music. I saw his band ‘Tangerine Puppets’ in a Forest Hills school auditorium talent show with John Cummings (Johnny Ramone) on bass. For some reason when we got out of high school in 1967, the Tangerine Puppets disbanded, Tommy said he thought I’d be good on bass. We were already going to concerts. We saw Cream, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix among a few.” So Monte and Tommy went to Music Row on 48th Street to Manny’s Music (made famous by musicians like Hendrix who hung around) and bought an imitation Rickenbacker bass. “Soon Tommy and I formed a power trio called Triad.” According to Tommy Triad was patterned after Cream and The Who.

Scientologist drummer George Goodridge booked shows that included a scientology gig in Washington Park. The handbills called them The Triad Blues Band and read “You can be more awake.” Director Author Penn was there scouting for a band for Alice’s Restaurant. Monte says of the gig, “We had to plug all our gear into a streetlight.”

The embryo of a tour manager was growing without recognition.

“Triad didn’t last long. Tommy went into engineering and I started playing with Thirty Days Out, a country rock band, did demos with Tommy and got signed to Warner Reprise. We opened for The Beach Boys, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Rush, etc. and were on The Mike Douglas Show. We put out two albums, Thirty Days Out (1971) and Miracle Lick (1972).”

Butch was the next attempt for Monte and Tommy and guitarist Jeff Salem. Known for his time with punk band Tuff Darts, Salem said of Monte, “He was the best musician in Butch.”

“Everything is meant to be,” says Monte. “My cousin was a locksmith and installed a lock in a loft on East 20th.” The owners were a musician and the other had lots of money. They wanted to turn the loft into a hip studio. There was a main stage, a separate booth with a glass wall for a four-track recorder, a rehearsal studio, offices and a lobby. “We built and designed everything by hand, but because we were in a residential neighborhood, noise complaints ultimately shut Performance Studios down.”

Sylvain Sylvain (New York Dolls) said, “David Johanson and I had rehearsed at Performance at the very end of the Dolls, right before we went to Japan for the final shows after Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan left.”

“People like Blondie were rehearsing there. I was working with a group called Smiley. We’d make flyers, charge a coupla bucks at the door, get a crowd, talk some label people into coming down and made our little score. I was doing the sounds and lights which Tommy taught me to do,” Monte says. “On the side Tommy was working on this unknown group, The Ramones.”

The Ramones started off as a trio; Johnny on guitar, Joey on drums and DeeDee playing bass and singing vocals. Tommy saw that DeeDee was having trouble singing while playing bass at the same time. He knew Joey had a good voice so he moved Joey off drums and up front, and they started to look for drummers. No drummer they auditioned could grasp what The Ramones were doing so Tommy sat in, and they asked him to join the band.

“They didn’t seem like anything promising at all to me, but Tommy saw something in them. When Tommy started playing drums, I couldn’t believe it. He was a guitar player for crying out loud!” Monte said of the early Ramone period before “tour manager” had even entered the vernacular. “At the time there was no word for it. But later, when they got onstage for that first time at CBGB and started their first song, ‘1-2-3-4’, there was something there.” Tommy was right.

Bob Gruen (Photographer) said about his first Ramones’ show, “I saw them play at Performance Studios. Even then they had the backdrop. They did 32 songs in 15 minutes and everybody looked at each other like, ‘What was that?’ It went by so fast we could hardly tell what happened.” Even Arturo Vega (Lighting, Director, and Merchandise, designer of The Ramones logo) with his multicolored shag had said, “It took about ten times before I was completely sure that they meant something totally different, a very radical change.”

Joey said, “We were one of the first bands to play CBs. When I found it, it was a slum bar that didn’t make it as a bluegrass bar. When I first spoke to Hilly Kristal, he said, ‘Nobody’s gonna like you guys, but I’ll have you back.’ There was this guy, Terry Orr, who was managing Television and giving them all the best nights. The first people we played for were the bartender, his dog and two guys from the Crokettes.”

But the audience grew to lines around the block after bands like Blondie, Talking Heads and all those who would relish later fame sat among the trash and Hell’s Angels beating the shit out of each other at the bar. John Holmstrom (Editor, Illustrator of Punk Magazine and Monte’s book cover) said the CBGB of ’75 and early ’76 changed later when they took the pool table and kitchen out to build a big stage and sound system.

Monte says, “I would run the sound. I didn’t know much about sound. Tommy knew about sound from working at the recording studio. At the early shows, he showed me how to run the board, just like he had shown me how to play bass. But I took to it real fast.”

At the time, punk rock of ’74 was Suicide, the Dictators, Television and The Ramones. Holmstrom thought The Dictators and The Ramones were gonna be like The Beatles and the Stones of the new revolution.

But the Summer of Rock Festival ’75 with publicity changed the audience from bartender and dog, other bands to full house. Tommy said, “This was the Bowery, and nobody went to the Bowery.” But the week or so of six bands a night and a full page in Rolling Stone solidified Monte’s and The Ramones’ future but not necessarily on the road to riches; more like the long and winding road.

Danny Fields (co-manager with Linda Stein) who had always had two jobs, one being with 16 Magazine and writing a column for the SoHo Weekly News said, “I thought the music of The Ramones was pretty much dealing with everything that the world needed then. You know, fill up that syringe and here’s my arm. Give it to me! Shoot me!”

Monte says, “The band signed with Sire in early 1976 in Arturo’s loft. They were very supportive. They gave them $6,000 to make their first record with the equipment Danny bought them.” Before the band got signed they hardly played out of New York, occasionally heading to Boston or Toronto with other bands like The Dead Boys or Dictators. But once their self-entitled debut album was released in May of ’76, the band hit the ground running as did soon-to-be tour manager Monte.

“My job changed and evolved. We went through different phases. In the beginning I was doing everything. I was roadie, I drove the van, I did sound and the monitors. It was a heavy job,” says Monte. One recollection from guitar tech George Tabb was how backstage, right before they had to go on, DeeDee would say he had to go to the bathroom and Monte would say, “DeeDee, didn’t I ask you before if you had to go?” “But Monte, I didn’t have to go back then. I have to go now.” School bus memories? “Joey, are you sure you don’t have to go?” “No, I don’t have to go.” Then Johnny would say, “Make him go, Monte.” Joey would say, “Tell Johnny to fuck off.”

So after touring the UK with bands like the Sex Pistols and Clash gathering at the club back window to hang with The Ramones and touring with opening acts like Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers or opening for Blues legend Johnny Winter, Black Sabbath to Blue Oyster Cult, double-billed in venues like the Santa Monica Civic with The Runaways, they had finally found their niche.

“Let me give ya an example of what touring Europe was like in the ‘70s for a bunch of New Yorkers. You couldn’t get ice,” says now tour manager Monte. “Let me give you a typical dumb thing that would happen on the road: we were all walking off a plane to go through Customs, when DeeDee realized he left his passport on the plane. From then on, I carried all the band’s passports when we went overseas.”

“Eventually we had a core crew when we toured Europe in 1977 with the Talking Heads,” Monte says. “Despite the culture shock and a coupla hairy moments, those first few European tours were very important for The Ramones. They established the band as head-liners and kick-started the UK scene.”

But what happened when the British Invasion attacked the US in the form of The Sex Pistols? For The Ramones who were in heavy rotation with MTV until MTV got popular and were pulled and the radio stations passing on interviews and playing their ‘60s inspired classic pop hits without the fluff because they were worried that a Ramone might puke on the board or onstage one might slash his wrists like thugs on the streets with a Cadillac tire, it just meant other acts went to the top without them.

“The Ramones were like the Johnny Appleseed of music,” Monte says. Why they never obtained the commercial success of their peers has yet to be written. But innovators don’t always get the rewards according to former Max’s Kansas City’s art and music director Peter Crowley.

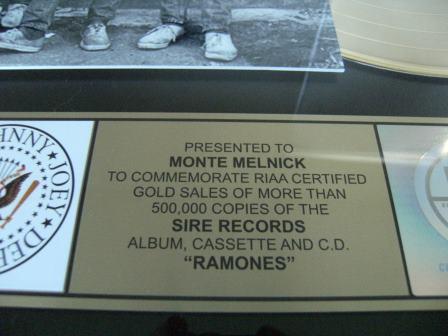

But the band needed a tour manager who could keep Joey’s OCD in check or Johnny’s staunch business approach from pissing everyone off more than it did or that the crash barriers were in place at a show so the band wouldn’t get trampled or the hotel accommodations were in check and on-and-on. Because Monte’s job was 24/7, he took the jokes like signs on the dressing room doors reading “No Melnicks” and didn’t bat an eye. He was there for 2,263 shows, The Ramones Tour Manager, The Fifth Ramone. After over a quarter of a century, RIAA certifies Sire Records “Ramones” first album, cassette, CD as selling 500,000 copies and they presented a Gold Record to Monte.

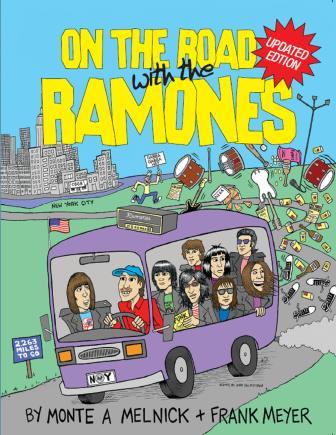

“Now you hear The Ramones’ music on Cadillac commercials and Hey Ho Let’s Go at baseball games. You got Green Day and Eddie Vedder and U2 as fans. They are in the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame,” says Monte. The must read On The Road with the Ramones by Monte A. Melnick and Frank Meyer IS the guide on how to be a tour manager. And speaking of The Ramones lasting power without the usual riptide of commercial success?

Crowley says, “It took the general public many years to be open to their sound. Now nearly everyone swears they were always a (Ramones) fan.” Gabba Gabba Hey!

https://www.facebook.com/monte.a.melnick http://www.amazon.com/Road-Ramones-Monte-Melnick/dp/1847721036/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1411410944&sr=1-1&keywords=ramones “On The Road with the Ramones” is also available in these language; Spanish, German, Hungarian, French, Portuguese & Italian. http://youtu.be/6q_mHFfOMWE http://youtu.be/TYh1lRR1m6Y http://youtu.be/zGgfHZ02I2k |

|

|