| |||||

|

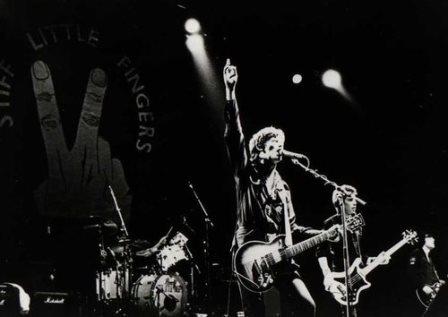

Welcome to Part 2 of my interview with Jake Burns of Stiff Little Fingers. Last month's article was a brief warm-up for an intense and stimulating conversation about depression, creativity, band dynamics, racism, oppression, and inspiration. Jake had so much to say that it didn't feel right to cram it all into one interview. Transcribing this gave me ten times the respect for a band who were already among my absolute favorites. Enjoy the read!

|

Punk Globe: "My Dark Places," one of the songs that you've played live, is about your depression and divorce. Would you mind taking us through the writing process for that one?

Jake Burns: It wasn't specifically written about the divorce, although the divorce was the trigger to a long period of depression that I went through. Up til that point, I'd heard of people who suffered from depression, I probably knew people who had suffered from it, but I didn't realize it because they were very good at hiding that sort of thing. I hadn't actually realized how disabling it is. I didn't want to anything, so that's why it took so long to write the song. I didn't want to get out of bed, didn't want to seize the day. People would call me up and say, "Hey, do you want to go out for a beer?" I went, "You know what, I'm just going to stay home," I started making excuses and lying. It was very cathartic to actually write about it. I had the idea for the tune first, which is unusual for me. When I write, I start with a really strong title so that I kind of know where the song's going to go. The guitar part for this one came to me one day when I was fooling around at the studio, so I recorded it. It followed a standard verse-chorus-verse pattern. Once I had the chords and the melody in place, I went, "what's it about?" I sat at the computer, played it over and over again, and started to feel helpless about the whole thing. I could feel the depression creeping up on me again. One minute I'm absolutely fine, the next minute, for no reason whatsoever, a dark cloud just comes over me. I started to write down how I felt and the only thing I changed when I felt better was that I went back and put a positive spin on the last verse. It is a serious subject, a lot of people suffer from this, and many people are embarrassed about it. It's not that you're being weak; it's just that you've been too strong for too damn long and you can't take it anymore. I'm sort of terrified of becoming a poster boy for depression, but I'm happy to stand on the stage and be able to talk about it and I'll talk about it to anyone who wants to bring it up afterwards. Talking about it made me feel better and I think it helps a lot of people to realize that they're not alone.

Punk Globe: Do you think that the song itself is part of that healing process?

Jake Burns: Like I said, it was cathartic to write it all down, and when we played it live for the first time, I put more energy into that one than most of the others. There is a feeling of being able to say, "Fuck it, I'm going to kick the thing's ass."

Punk Globe: You've also got the song, "Trail of Tears," on the new album, which is about the immigration laws in the southwestern U.S., right? Can you tell us about that?

Jake Burns: In Arizona, they said that they were going to stop people who looked like they could be illegal immigrants in the street and demand identification. That just seemed so wrong to me. Every country in the world has an illegal immigrant population, but to actually stop people and demand to see their papers while saying, "No, this isn't fascist at all," is absurd. Have these people ever seen a World War II movie? "Show me your papers," was one of their catchphrases! There are a lot of positives to living in the U.S., but it seems like the divide between those who have and feel entitlement and the rest of us is getting wider all the time. It's one thing if somebody has a bunch of guys working on a construction site and they're not insurable because they aren't citizens and they don't have Social Security numbers, but to just stop someone on the street because you don't like the color of their skin is pretty fascist. It's scary because you don't know where it's going to stop.

Punk Globe: Did hearing about that remind you of the situation in Northern Ireland when you were younger?

Jake Burns: Yeah, there were situations where you'd be stopped at roadblocks and asked for identification. When you went into the city, there was what they referred to as, "The Ring of Steel," which was where they put security gates at every entrance, you had to line up, you had to be searched, it was almost like going through airport security. If anyone had a bag, the bag would have to be checked. Once you'd gotten through that, all of the stores would hire private security and you'd get searched again. It became second nature whenever you walked into a store, you would stand there with your arms outstretched and be patted down. When I first moved to London, I kept walking into stores and standing there with my arms outstretched. People were looking at me thinking, "Is he gonna start singing, what the hell's wrong with him?" There are definitely parallels, but the difference is that in Northern Ireland, there was a civil war going on, so you could see the reason why some people were carrying bombs. That would be taking it to an extreme, I think.

Punk Globe: When I saw The Specials play back in July 2013, they played, "Doesn't Make It Alright," and dedicated it to Trayvon Martin. Have you done the same when you've played your version live?

Jake Burns: No, we haven't. We haven't played here in the U.S. that much. Obviously, it's their song, we just stole it. I think that the song speaks for itself. If they were there around the time of the trial, they knew that it was in the news and that it was a salient thing to say. Something like that is exactly the kind of instance that the song was written about. It was written in 1979 and it's been a problem since one group of people said that they were superior to another group of people. It's been centuries and as much as we'd like to think that we're more enlightened than the slave traders back in the 1700's, you can't excuse racism on any level. We know how the system still exploits race on a large level. It happens, and you need songs like that because they're a very useful way of highlighting a problem. Chances are fewer people are going to read a university research paper about racism and its causes than are going to listen to a rock song. Anything at all that you can do to call attention to a situation where people are dying or circumstances are unjust is useful.

Jake Burns: I've always tried to point out issues, but I don't really see it as education. I try not to be too preachy and not say, "This is what you should do." It's more like a photographer or a journalist documenting what's going on and leaving it to the audience to make their own minds up. Our approach more a case of, "Look, this is happening, are you happy with that?" A song like "Doesn't Make It Alright," definitely says, "We're not fucking happy with that." There are certain constants and certain absolutes in life that you shouldn't be happy with and racism is one of them. It doesn't make sense on any fucking level at all. There a lot of other things that upset my sense of justice that other people might possibly see justification for, not everything is absolute like that.

Punk Globe: In looking up some live videos recently, I found Henry Cluney and XSLF. How do you feel about them?

Jake Burns: It's no secret that Henry and I have butted heads over what seems to be his re-writing of history, but he's entitled to his memory and I'm entitled to mine. Nobody should have any problem at all with anybody trying to make a living. Henry did play on those frecords; he and Jim have every right to play the songs. Anybody has a right to play the songs, that's why there are cover bands. People do that all the time. I felt that some of the criticism that he was leveling at us was unjustified. As far as he was concerned, the band ended when Jim left. If that was the case, why did you hang around and make another two albums with us? He claims he's playing the songs that people want to hear. Well, the songs he's playing, I wrote. If you're going to say that what we're doing is somehow devalued, don't play the songs you weren't involved in writing, play the ones you wrote. Realistically, if he were to do that and is only talking about the first three albums, he's only got about six songs. That's a pretty short set. I don't want to get into slinging mud with them; I'm not going to stand in anyone's way who's trying to make a living playing music. It's important to stick to some semblance of the truth when you're talking about the other members of the band.

Punk Globe: "Strummerville," which came out just about eleven years ago, is about a hero of both of ours, Joe Strummer. What were your thoughts ten years after Joe died?

Jake Burns: It was ten years since Joe had passed when we were going to make the record. Obviously, I was being asked for memories of Joe and The Clash and stuff like that. I didn't know Joe well at all, only met him a couple of times. We were almost ready to go to the studio. I wrote it the night before the final rehearsal. He was on my mind and the effect and influence that he had on me felt strongest that night. We had the same job, you know, we were both at the front. It wasn't just the music that influenced me or the political stance, even though they were both very important to me. The thing that really impressed me and hopefully something that we've carried on and brought into our career was the way he treated his audience. The Clash played in Belfast, and at the time, Belfast was a powder keg. There were still bombings and shooting in the streets. The city fathers jumped all over this and said, "Don't we have enough trouble? We don't need punk rock bands. They cancelled the insurance on the night of the show, so The Clash weren't allowed to play. There were hundreds of us waiting outside of the venue being told they weren't playing. In any other city in the world, people might have complained, demanded their money back, or just shrugged it off. In Belfast, of course, we rioted. Somebody tipped us off as to the hotel that the band was staying at, so people decamped to the hotel. As I said earlier, about the stores, hotels and bars also had the metal gates and cages and CCTV. It wasn't like thirty angry punk rockers could storm into the hotel and start yelling at the band. We were given no information at all, so we didn't know why the gig had been cancelled. Joe and Paul came out and talked for hours with anybody who wanted to talk to them. I sat and watched them thinking, "He didn't need to do that!" He could have come out, said the insurance was cancelled, and went back in. He could have even stayed in the hotel. It was the fact that took the time to do that and was receptive to questions that really inspired me. Some people who were there look back on that night as almost better than when The Clash came back a couple months later and actually played. That made me think that if we ever got to any sort of position of prominence that I'd never forget that night. Everybody has an off night where maybe they don't want to do it; everybody gets a cold on tour at some point. You feel like crap and you just want to go back and sleep, but you have a great conversation with someone who you've never met before and you realize that's part of our job as well.

Punk Globe: Have you ever had to go out to a crowd and assuage a tough situation?

Jake Burns: Yeah, just this past March. We were playing in Lancashire, England and we were just about to go onstage and Ali turns to me looking white as a ghost and said, "I can't do this." It turned out that he had food poisoning, but I could see that he was shivering and I was really worried. He said, "If I can sit down, I might be able to do the show." Sitting down is not Ali's thing, I mean, he's like Tigger, he just bounces around all over the place. We got about 5 or 6 songs in and Ali yells, "I've got to go," and runs offstage. He just about made the dressing room before he projectile vomited everywhere. The first thing we did was check that he was okay, then we went back out and spent the rest of the time talking to people about what had happened. People are reasonable if you let them know that there's a problem. Not one person said, "Oh, you're making it up." We could have all just gone back into the hotel, but that would have meant people would have left with no real understanding of what had happened and they'd have a right to get angry. If you've just paid not only the cost of the ticket, but the cost to get there, babysitters for some, and maybe a meal and a few beers. This is a night out and suddenly the night out stops. Because we talked to them, we got nothing but messages of support. We played a makeup date in May. Hopefully, you don't have to do it that often, because if you do, it means something's gone terribly wrong.

Punk Globe: What's been the biggest difference having Ali back in the band versus having Bruce Foxton?

Jake Burns: They're two very different players. Bruce is very concise and on the money and a great singer where Ali is much more theatrical and readily admits that he's not a great singer. We had a lot more use for vocal harmonies when Bruce was in the band. When Bruce left we lost that aspect of the recorded sound and the live shows, but what we got back was a huge injection of enthusiasm. Ali had been there right from the start, so it took a while for me to get used to it again. The other three guys were a lot more comfortable with him being in the band, whereas he and I were like, "Okay, I've known you since I was 17," and we danced around each other for a while. Looking back at it, it was nice because we were both terribly polite to each other. It took a couple of tours before we were back to, "Get out of the fucking way!" Everything was cool again. As well as being hugely enthusiastic about what he does, he's very professional. He absolutely loves it, which is worth its weight in gold because there are days when I feel like death and don't want to do it. He'll be the first one to come over to me, punch me in the shoulder, and say, "Come on, let's do this!" That attitude is infectious; everybody in the band picks up on it.

Jake Burns: That's a very good question. I'm more nervous these days than when I was a kid. When you're that age, you think you're indestructible and everything you do is fueled by enthusiasm and hope. These days, there's more of an expectation on the crowd's part, because they know what you're capable of, and if you don't deliver the right sound to them, you get a tepid reaction. Very rarely does anyone come up to us and tell us we sucked, but they might tell us liked us better last year. The other thing that's got me nervous onstage now is that I know what can go wrong. If something can go wrong, we've had it happen before. If I hear and odd noise or see something move out of the corner of my eye, my first instinct is to go, "Oh fuck, what's that?" We've done it for so long that there's a danger of doing it on autopilot. With Ali's enthusiasm, though, we don't have to worry about that as much. I still get stage fright before we go on, in fact, I get worse stage fright now than I did when I was younger. I very rarely want to talk to anyone before we go on, I get knots in my stomach, and it's not that I'm being aloof or rude, it's just pure nerves. The minute my foot hits the stage, I feel fine. It's the weirdest feeling in the world. I should probably talk to a psychiatrist about that.

Punk Globe: What was the first gig that you played where you stepped onstage and felt at home?

Jake Burns: It's hard to tell because I don't know how much of that you'd credit to the band being successful. I can't think of any one defining moment, but it would've happened around the time of our first major support tour for The Tom Robinson Band, who were really big in Britain at the time. Because they were so popular, every show on the tour was sold out, which meant we were playing to very partisan crowds. If they even know who we are, they don't want to hear us. We started getting called back for encores on that tour. In fact, I think there were only two nights on the entire tour where we didn't get called back. It was around then that we all started to believe that we weren't the useless little bastards from Belfast that we thought we were. It's very much a Northern Irish trait that you never actually admit to being any good at anything. You're never allowed to get above yourself and I think that's engrained in our ethic, so when we started getting validation from somebody else's audience, we became Sally Field and went, "You like us, you really like us!"

Punk Globe: The Tom Robinson Band had that single, "Glad to Be Gay," which was really controversial at the time. Did your family have any objections to you going on tour with them?

Jake Burns: Yeah, my mother was convinced that I'd be lured into a world of homosexuality when I went on tour with them. I said, "Ma, you can't catch gay. Trust me."

Punk Globe: I read some of your comments in interviews from 2007-2008 about your support for Barack Obama, how do you feel about him now?

Jake Burns: Disappointed. The guy just seems ensnared at every turn. I was excited about him then, especially living in Chicago. As much as he's been hindered, he also could have done a lot more when everything was there and the tide was in his favor. I'm not a politician, I don't know what's involved in their decision making process. On Capitol Hill, people seem to put as many roadblocks as they possibly can in someone's way. He's sort of fallen prey to that and now he's just kind of treading water. I think he's had a great opportunity that's being missed somewhat. There's been some good stuff that's gone through, but a lot of people who believed in him, myself included, are let down over all. The man's heart is in the right place and other forces have stopped him from doing more. That's the way it is with a lot of politicians here and in Britain and Ireland. These people are elected to supposedly work for us and to make our lives better. That's what everyone promises and that's why we vote for them. Those noble aspirations quickly become two sets of adults acting like kids in a playground. This isn't kindergarten, they're supposed to be running the fucking country! When we got rid of Bush, I thought, "At least now we have a president who's smarter than I am."

Punk Globe: With the build-up of the national security state, do you think that songs like "Suspect Device," take on new meaning?

Jake Burns: I get where you're coming from with that because I wrote it about a heavily enforced police state, but if you see direct parallels with that, that's pretty scary. Hopefully we're still a ways away from that, but you never know what's going on behind closed doors. I hoped that those older songs would become like folk songs. Like, "Oh, remember the bad old days when these were relevant." Sadly, if the songs are still relevant, it means we have similar problems.

Punk Globe: How do you hold onto that feeling of hope you might get from a Stiff Little Fingers show and make something out of it in your daily life?

Jake Burns: That's up to the individual. Stiff Little Fingers is my daily life. With regard to what others get from it, I can only go from the people I've talked to who say they get some amount of energy from the show and that carries them through. Like you said, people still find relevance in our lyrics. We always try to finish the set on an optimistic note and say, "Yes, its shit, but it doesn't have to be like that." I think that's what people pick up on.

Punk Globe: Thank you for a wonderful interview, Jake. Do you have any words of wisdom for our readers?

Jake Burns: Oh, Lord. You've definitely come to the wrong guy for words of wisdom. The one thing someone said to me that sticks with me is that this is your one shot at life, you can take advantage of it and do what you love when you find it or you can go ahead and fuck it up. I know which one I'm going to do. First and foremost, I'm going to try and enjoy it and make the best of life.

|

|

|